Obtain our opinion/offer/free valuation.

Simply fill in the form or email- davidmatteybuyer@gmail.com

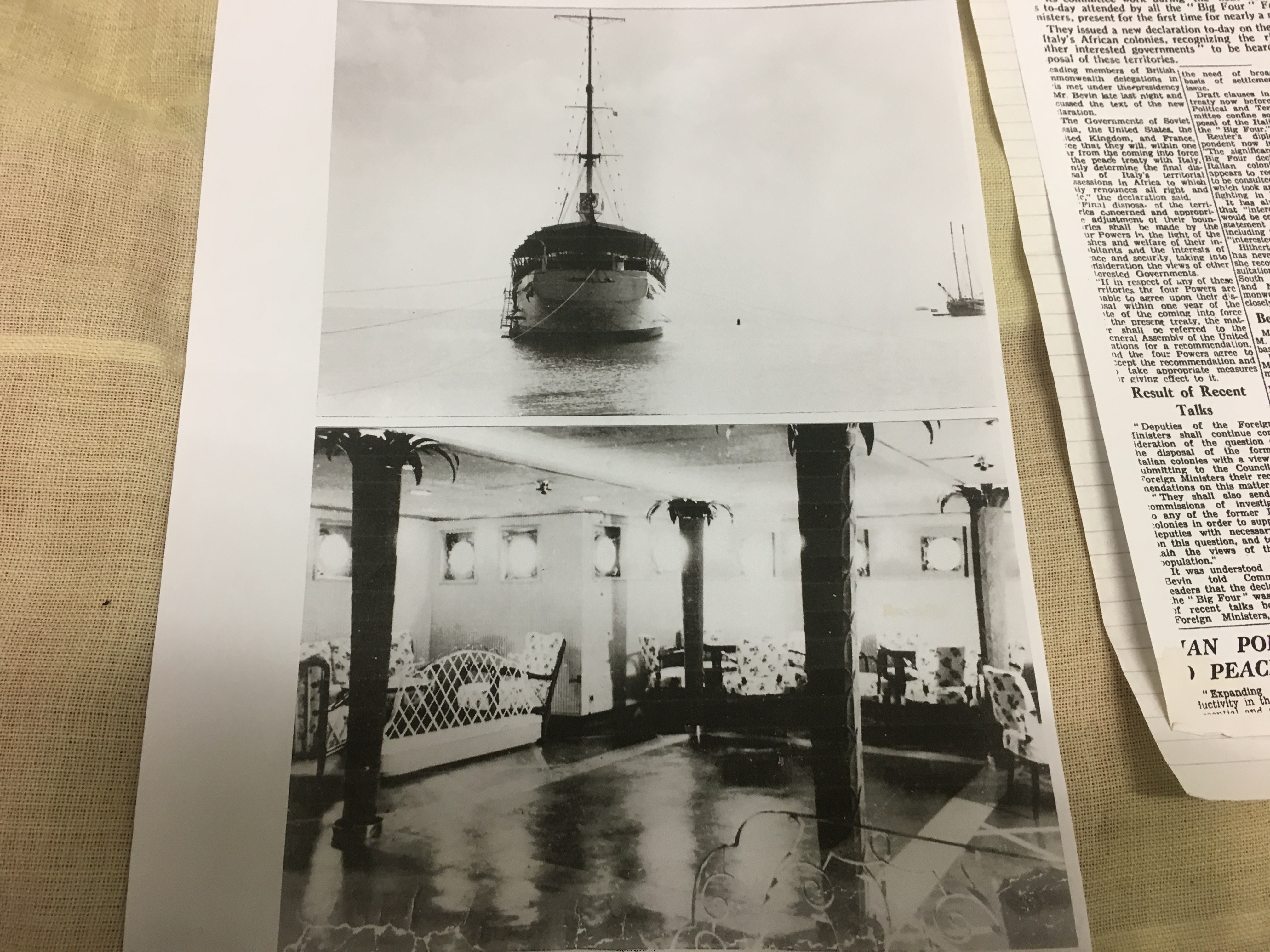

AVISO GRILLE

(1935-1951)

In July 1940 a couple of weeks after the fall of France, the German Navy began plans for Operation Seelöwe (Sealion), the invasion of England along a 275-mile front from Ramsgate to Portland.

STAGE ONE of the plan was to overwhelm the British fleet in the North Sea and English Channel, followed by the occupation of the southern counties of England.

STAGE TWO was for Hitler’s triumphant arrival in the Port of London on board a suitably royal yacht, the Aviso Grille, to receive

Britain’s surrender at Whitehall.

STAGE THREE of the journey was for the Führer to travel along the river Thames on board one of Grille’s three pinnaces, Motorboot 1 later to become known as Grillet.

After the victorious arrival in London, Hitler was to proceed without delay by motor boat to Windsor Castle, already earmarked as his ‘London home’. In preparation for the conqueror’s voyage of victory, Grille, with Grillet on board, had been moved from the Baltic to Belgium and made ready in Ostend.

This would not have been that ship’s first visit to the

Thames. At the outbreak of war she had been laying mines in the Thames Estuary, the first German surface vessel to enter British territorial waters after the outbreak of war.

Although Hitler was subject to seasickness and not a confident sailor, his choice of arrival was intended as a mark of respect for the Kriegsmarine and to signal to the world the defeat of the Royal Navy. This is the story of Grille, and of Motorboot 1 now known as Grillet.

Motorboot 1 in background

The Aviso Grille carried three smaller boats on her decks during the war. All were built by the Lürssen yard at Bremen in 1934. Lürssen, the first shipyard to build diesel-powered boats, designated them as Motorbooten 1, 2 and 3. They were used as pinnaces and admirals’ barges. In March 1934 the great shipyard Blohm & Voss in Hamburg laid down the keel for a new ship, the yard’s 500th vessel. ‘Fleet Tender C’, was to be christened later as the Aviso Grille. Earlier vessels had borne the same name, the most recent being Kaiser Wilhelm’s royal yacht. At the time of her launch on December 15, 1934, Grille at 443-feet overall, was the largest yacht afloat. The Aviso is generally a dispatch or intelligence ship and in spite of being built (at a cost equivalent to more than a million pounds, raised partly by public subscription) as Germany’s equivalent of a royal yacht, she was equipped with three 12.7cm cannon, six anti-aircraft guns, two machine guns, and the capacity for carrying 280 mines. Grille is usually translated as “grasshopper” or “cricket” but a secondary interpretation is “whim, fancy, caprice” and, at least to the English ear, Caprice seems by far the most appropriate name for a stately yacht.

Grille was the first ship to test the high pressure steam machinery planned for German destroyers. According to the diary of a former crew member, Kapitänleutnant Helmut Krämer, “The complicated engine design of the ship demands a high degree of technical competence to maintain immediate readiness for service. The drive-shaft turbines run with 400 degrees of superheat. The boiler system of the ship is automatically controlled by an Askania-Anlage system, it is a new and untried power design and we in Grille carry out trials in anticipation of similar engines being installed in all new destroyers. We live in a permanent state of stress.”

Krämer was one of four “Jacob’s-ladder men“, junior officers who, in addition to their regular naval duties, looked after VIPs, usually arriving alongside the ship on board Motorboot 1. The team members had to be 1.8m or more in height and wear white uniforms. There was a modern laundry with ironing machine on board. They were often in close contact with the Führer and his staff. Important secret conferences of the Naval Command took place.

“We were subject to the strictest security measures. The visitors were leading personalities of the Third Reich included Göring, Hess, Göbbels, Himmler and honoured visitors from Hungary, Italy and Japan. Hitler was the most frequent visitor, showing off his ship and usually spending three or four nights on board but not often venturing far out to sea.”

Hitler aboard the Aviso Grille

According to another Kriegsmarine officer: “Hitler had little understanding of naval strategy, though he often memorized small details of a ship to humiliate his admirals when they couldn’t answer his every question.”

Apparently life on board could be stressful for VIPs. Interrogated after capture by the US Navy in July 1943, Kapitänleutnant Klaus Bargsten, sole survivor of U-521, reminisced about serving as a midshipman on Grille. Once, he said, when a group of these ‘Olympians’ was on board, an orchestra was playing for their entertainment, but the ship’s ventilator fans were making so much noise that the music could scarcely be heard. Göbbels complained to the captain in his usual high-handed manner, ordering him to do something about it. The captain, while engaging Göbbels in conversation, managed to back him into position in front of one of the ventilators. When he gave the order for the ventilators to be shut off, the shutter gave Göbbels a resounding whack on the backside.

Bargsten also spoke somewhat heretically about the alcoholic habits of the Nazi great. Hitler, he said, objected strenuously to drinking and often gave his staff violent temperance lectures. Shortly after having been subjected to one such harangue on board the Grille, the staff gathered in the saloon to sooth their frayed nerves with a bottle of Champagne. Suddenly Hitler appeared in the doorway and the bottle, which had just been opened, was discreetly hidden beneath a table. Hitler strode into the room, kicked the bottle, spilling its contents, turned on his heel, and walked out without uttering a word.

In addition to the fleet reviews and engine trials the boilers did not permit sufficient maneuverability to satisfy Blohm & Voss, so were not fitted to other warships Grille was employed in peacetime for navigation and artillery instruction, and as a target ship for U-boats, all uses requiring regular voyages in the North Sea and the Baltic. But whenever she was required for state duties, Grille was summoned back to Kiel or Hamburg.

Her first appearance as a state yacht was on May 30, 1936 for a fleet parade to commemorate the Battle of Skagerrak. Then Hitler and his War Minister, Field Marshal von Blomberg, went on a short cruise to Reykjavik. For writing home, crew members were entitled to use dapple-edged postcards picturing the ship, and a special edition of the card, bearing the signatures of both von Blomberg and Hitler, was produced to commemorate this momentous voyage. In fact the Führer spent most of his time on board being seasick. The following year she carried the German delegation, led by von Blomberg, to England for the coronation of King George VI on May 12 and to observe the Royal Navy’s Spithead Review which started gathering in the Solent, near Portsmouth, the following day. In October that year she conveyed von Blomberg on a voyage into the Atlantic, putting in at Funchal, Madeira and Porta Delgada.

In his memoirs Hungary’s regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy, recalled an invitation to visit the Germania shipyard at Kiel in the summer of 1938:

Hitler had bethought himself of a signal honor to pay me. In my distinction as the last Commander-in-Chief of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, the traditions of which were now proclaimed by the German Navy, I was to attend the launch of a heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and my wife was to christen the vessel.

My wife, accompanied by a party of ladies and several other guests, had gone on board the elegant HAPAG liner Patria. Hitler and I went on board the control vessel Grille, which Hitler used for his sea trips. The naval review that was held displayed the surprising number of vessels possessed by Germany, considering the short space of time she had had to build up her fleet.

Kapitänleutnant Werner Lott, commander of U-35, was to recall that, exactly one year later, around August 20, 1939, “We had held exercises with all our U-boats in the deeper waters of the Central Baltic Sea for a maneuver that Hitler had ordered to show off to the king of Italy on his state visit. Hitler had been impressed on his official visit to Italy May 1939 by a rather static display of submerged power in Naples Bay and now wanted to impress him with daring and very mobile maneuvers. All went well on this exercise around Hitler’s Aviso Grille and thereafter we all entered Swinemünde Harbour. There the U-boat captains were invited to lunch with him on board Grille where C-in-C Räder presided and Dönitz was also present. After lunch a most unusual thing happened. Räder rose, made a few complimentary remarks and then said “Have you any questions?” I knew him well and shot without a second’s hesitation the question at him: “We cannot help feeling that we are drifting towards war – is that really unavoidable?” And he also answered without hesitation: “Hitler has so far achieved so much in his six years in power that I do not think he will risk all the positive achievements in a hazardous war.”

Two days later Grille was laying mines around Wilhelmshaven…

Three years after the visit of his former king and three years after the start of “a hazardous war“, Mussolini attended the launch of the world’s then biggest battleship, perhaps predictably named Führer, and was taken out for a celebratory dinner cruise on board Grille in the Baltic, his host (according to one officer) being particularly pleased that “on this occasion he had not felt the slightest bit queasy.”

On the Führer’s orders the ship had not been camouflaged for war, but had retained her distinctive yellow funnel and white hull with gold paint on the bow and stern. He referred to the ship as “The White Swan of the Baltic”. But Grille, in the interim between state visits, had nevertheless switched roles from royal yacht to warship.

When Hitler¹s army invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, he sent a message ordering that ‘his’ ship be prepared for combat. Mine-laying equipment was fitted along the decks and the mines themselves loaded at Wilhelmshaven. In the evening of September 3, and for six nights afterwards, Grille, with a destroyer squadron for protection, laid mines in the North Sea. Krämer recalls that “In the Thames estuary the navigation lights were still shining. Back in Kiel, Grille took on more ammunition and mines in preparation for the occupation of Norway. Hitler had decreed that his ‘own’ ship should lead the invasion, and the fleet sailed up the Danish coast with Grille in the van. En route, and still in waters protected by German minefields, Krämer suddenly heard “a crack and a crash in our own ship. My first thoughts were that we had hit one of our mines.” Throughout the ship, people shouted and alarm bells rang. It was exactly midnight. They had not, however, struck a mine but, precisely as the watches changed, they had rammed a Danish freighter, which now “literally hung from our ship”. They transferred the distraught merchant sailors on board, then brought round the ship and lowered Motorboot 1 to look for more survivors in the water. The crew saw what looked like hundreds of floating, naked bodies but when they came close and started to haul them on board the crew discovered that they were not people but pigs, “wriggling and making the most dreadful squeals and screeching”, which were to have been part of Denmark’s export trade. Grille had been holed by the collision and was shipping water, so had to return to Kiel for repairs, thus being denied the glory of leading the assault on Norway.

“We had, however, sunk 300 pigs,” noted Kapitänleutnant Krämer, philosophically. Back at sea, Grille fired a shot across the bow of another Scandinavian merchant ship and captured it; this one was carrying cellulose bound for England. Ten of Grille’s commandos, armed with rifles and pistols, were conveyed to the ship by Motorboot 1 and boarded her and escorted their prize back to a German port. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew sat in the freezing Finnish Gulf, waiting for their relief. Ice floes surrounded the ship and thick sheets of ice covered her decks. Heating oil and food supplies ran low and eventually Grille, with a thoroughly dispirited crew, hungry and living in unheated quarters, put in to the nearest German harbor, where the bunkers were refilled and provisions replenished and the ship made ready for her next mission: Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of England.

Hitler’s battle plan, from conception to fulfillment, allowed for 80 days preparation (as a comparison, the D-day landings took two years to organize). The invasion envisaged the use of ten infantry regiments, 170 cargo ships, 1,277 Rhine barges, and 471 tugs, which were all gathered alongside Grille in Ostend. Even allowing for the fact that the barges could not operate in anything other than a dead-calm sea, and could be overturned by the mere wash of a Royal Navy warship, it was impossible for mobilization on such a scale to escape the notice of the RAF. The operation has been described as “perhaps the most flawed plan in the history of modern warfare”. Says Krämer:

We were frequently bombed, and hid in the cellars of bombed houses. On board were only the flak gunners. In the harbor, it looked dreadful; everywhere were burning ships and boats. All the docks were damaged. There was no water; everything lay in rubble and ash. Suddenly Sea Lion was called off. We were undamaged, and we sailed away from Hell, back to Kiel.

Hitler then switched his sights towards the Soviet Union and Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia, with Grille again leading the mine-laying maneuvers.

Thereafter, Grille enjoyed a relatively peaceful war.

In 1942 she was painted wartime gray and used as the staff ship and operational headquarters for Grand Admiral Erich Räder, C-in-C of the Navy, based mainly at Narvik. The Battle of the Arctic was controlled from her dining room. When Räder was replaced by Karl Dönitz Grille became command ship of the U-boat fleet.

On May 1, 1945 Grand-Admiral Dönitz was ferried by Grillet to Grille and there on the foredeck he announced the death of Hitler. It is recorded in the ship¹s log “that he, acting on the Führer¹s orders, had assumed leadership of the German nation and supreme command of the fighting forces.”

The last German entry in the log was: “May 2-4: Flag at half-mast in memory of the hero’s death of our Führer“. A few days later Grille, by now with patches of rust showing on her gray hull and with only one working boiler (the engines were reported to have been sabotaged), sailed from Trondheim. With her German crew commanded by British officers, she anchored in the Forth at Rosyth a prize of war. Too big to stay in a busy port, she was then towed to the grimy and far less dignified coal dock at Hartlepool, County Durham, and, a year later, offered for sale to the highest bidder. There was no reserve price, but the Treasury was reported to be hoping to achieve a figure between GBP 70,000 and GBP 100,000, which it considered “cheap at the price.”

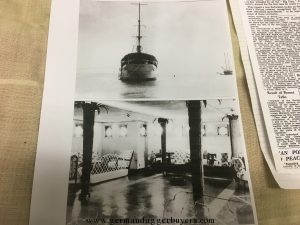

Paying visitors were allowed on board her. They were shown 35 luxurious guest cabins and the crew quarters, the all-electric galley, the laundry, workshops, sickbay, and the plant that could desalinate 24 tons of water a day. They searched almost in vain for the sign of a swastika: there were in fact only two, one on the stern as part of the emblem of the Kriegsmarine, and another on the ship’s bell. Hitler’s suite was the main attraction, with an ante-room, a bedroom and a bathroom. The bath was set flush to the floor. There were carpeted floors, a desk, sofa and chairs, all upholstered in eggshell-blue with off-white paintwork. Across the companionway was an exact duplicate suite with rust red as the dominant color. Visitors were told this was the “boudoir reserved for Eva Braun” but, although this would undoubtedly be a good sales pitch for potential purchasers and tourists, there is no record anywhere of her ever having been on board.

In August 1946 the Admiralty announced that a buyer, a Canadian ship owner and financier living in Byfleet, Surrey, had paid about GBP 125,000 for her and planned to sail her around the world promoting British exports. Two years later the ship was again offered for sale, now with an asking price of GBP 400,000, and eventually bought by Mr. George Arida, a Lebanese textile manufacturer, for a reported price of GBP 357,000. Mr. Arida who, during the war, had provided the material for tropical uniforms for British troops and also personally paid for the construction of an RAF Spitfire, was secretly representing King Farouk of Egypt, who did not want to be publicly associated with the purchase of “Hitler’s yacht.” En route to Beirut, with a senior Blohm & Voss engineer on board, saltwater was discovered in the cooling system, and Grille had to put in to Malta for repair.

In Beirut, anti-Farouk terrorists attached two limpet mines to her hull, causing only minor damage. But the king suddenly lost interest in his purchase, leaving Mr. Arida, who loathed the sea, stuck with both the ship and the bill. Grille was steamed to New York, where Mr. Arida hoped to find someone interested in converting her into a luxury cruise ship or floating casino and she briefly again became a tourist attraction at a dollar a time on a berth described as “near Wall Street.” But, with her berth costing GBP 250.00 a day, she had become what Mr. Arida described as “an expensive toy.”

In April 1951, four years after he had bought her, he sold Grille for scrap for GBP 35,000 less than one tenth of what he had paid and the vessel was towed to a yard on the Delaware river to be broken up and the metal recovered from her used in America¹s defense program.

Meanwhile in Hartlepool, Mb-1, which had become known as Grillet, using the German diminutive, made available by the Royal Navy for service as a race rescue tender for the local yacht club.

In 1946, when Grille was first sold, Mr. Tommy “Tot” Richardson, commodore of the club, acquired Grillet in exchange for a new Austin Ten car. Mb-2 was bought by a fisherman who planned to use her for passenger trips on the Moray Firth and Loch Ness. Mb-3 was bought by a farmer in Poole, on the Dorset coast, who sold her in 1969. Extensive inquiries have failed to trace Mb-2 and Mb-3.

“Tot” Richardson sold Grillet in 1966. She was sold again in 1974, after which she spent several years as a weekend pleasure boat, moored on the River Ouse at York. Then she turned up as a fishing boat in the Humber estuary. In 1986 she was acquired by Mr. Ian Slack, a Rotherham engineer, for use as a family cruiser. He moored the boat at the village of Heck, near Doncaster a long way from Hell (via Kiel).

The current owner bought Grillet from Mr. and Mrs. Slack in 1999 and has since cruised her in the Mediterranean. He completed a refit in 2007 which included a new marine oak keel and fitting stabilizers and hydraulic steering.

|

Revel Barker at the helm of Grillet

|

Grillet moored on the River Thames at Penton Hook, near Chertsey, Surrey, during a refit in 2001.

The marina is the closest that Motorboot 1 ever got to Windsor – just 10 miles away.

Grille today

Aviso Grille Data

Laid Down |

06.34 |

Launched |

15.12.34 |

Commissioned |

19.05.35 |

Shipyard |

Blohm & Voss, Hamburg |

Length |

135.0 m |

Beam |

13.5 m |

Draught |

4.20 m |

Tonnage |

3,430 tons |

Machinenery |

4 Benson high-pressure steam boiler, and later reconstruction |

Performance |

|

Speed |

26 knots |

Driving range |

N/A |

Armour |

N/A |

Armament |

3 x 12.7 cm guns

|

Crew |

|

Commander |

05.35 – 05.38 Cdr. Helmuth Brinkmann05.38 – 06.40 KzS v.d.Forst06.40 – 10.40 Lt.Cdr Poske11.40 – 03.42 Lt.Cdr Lanz03.42 – 08.42 out of08.42 – 05.44 Lt.Cdr Just05.44 – 05.45 KLt.dR Ludloff |

Remaining |

1945 by the UK,1946 sale to a company in Lebanon for cruises in the Mediterranean,11.47 damaged in Beirut08.49 Sale in the USA,1951, scapped in Sydney |

WE PAY YOU MORE !