351st Bomb Group

by admin | Mar 19, 2017 | alles fur deutschland, alles fur deutschland dagger prices 2, alles fur deutschland dagger value 1, alles fur deutschland dagger value 2, antique sword dealers, August Bickel, banned from ebay, Best buyers of WW2, General Assault Badge, german daggers, German Helmet, German Militaria, Giesen & Forsthoff, Gottlieb Hammesfahr, Government officials, Hitler Youth Leaders Dagger, Kenneth Daniel Williams, Luftwaffe, Paul Weyersberg & Co, Paul Weyersburg, Postshutz dagger, Proffesional Valuation Of German Daggers, R.A.D., Reichswehr, Robert Klaas, Robert Klaas, S.A. Dagger Valuations, Solingen-Ohligs

The Saga of Murder, Inc.

A German Propaganda Victory

by Kenneth Daniel Williams – 351st Bomb Group

During World War II, I was a bombardier with the 8th Air Force flying out of England. I was shot down over Germany wearing a flight jacket with “Murder, Inc.” written on the back. The Germans made much propaganda out of this.

At the request of a group in Holland, the “Bulletin 1939-1945, Airwar Study Group Holland”, I am wring down here the events that took place in relation to “Murder, Inc.”

Mehr sein als scheinen

Contrary to some of the German propaganda, I was not a Chicago gangster. I was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.A. on May 16, 1922. I attended local schools and went to Belmont Abbey College, an institution run by Benedictine Monks, many of whom came from Germany.

Freiwillige

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and every young man that I knew was anxious to join the armed forces to defend his country.

Nazi Artifacts

In June of 1942 I joined the United States Army Corps of Engineers and advanced to the rank of corporal. In December I transferred to the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet program.

Schutzstaffeln

Having been an enlisted man, I wanted a commission as soon as possible. To become a navigator took twelve months, a pilot, nine months, and a bombardier, six months. I applied for bombardier school and received training in Midland, Texas. After graduation I was assigned to Geiger Field, Spokane, Washington for phase training. This is where our crew was formed and trained to operate the B-17 heavy bombardment aircraft.

In October, 1943, we flew to England and were assigned to the 351st Bomb Group, 508th Squadron. We were assigned the B-17 “Murder Inc.” It was an old plane that had been on many missions and I have no idea who named it or why it was given this name.

As it turned out, we never flew a mission in this plane. It was the custom to have the name of your plane painted on the back of your flight jacket. One of the enlisted men came by my room and asked if I would like to have the name of the plane painted on my jacket. I told him “yes” and gave him the jacket. He came back the next day with this jacket painted.

As it turned out, I was the only member of the crew whose jacket was painted before we were shot down in, ironically, another plane.

On November 16, 1943, we flew our first mission to Knaben, Norway, to bomb a heavy water plane, part of the German effort to develop the atomic bomb. “Murder Inc.” was in the hanger for repairs and we flew in a new plane that I believe had not yet been named.

This was about the time they quit painting B-17’s, and the one we flew that day was the original aluminium color.

We had trouble transferring fuel from the bomb bay tank to the regular tank on that mission and thought we might have to land in Sweden. The flight engineer finally corrected the problem and we flew back to England through the worst weather I have ever flown in.

On November 26, 1943, we flew our second and last mission to Bremen, Germany. We arose about 4:00 A.M. and had eggs for breakfast. Eggs were a treat reserved for mission days only. From the mess hall we went to the briefing room to have the mission explained and to synchronize our watches.

Next we went to the “dry room” where the parachutes and heated suits were kept. I found that my parachute was being repacked and they gave me the parachute of a man over six feet tall. I am 5 feet 8 inches. I did not adjust the harness but just put it on and let it hang loose. The type parachute we used was developed by the British and was called a “clip-on chest pack.” One wore the harness all the time in the air, but the actual parachute itself was folded up in the neat little package that could be clipped on the chest of the harness if ever needed. I always kept my parachute on the floor close to me in the nose compartment of the aircraft.

We put on electrically heated suits for warmth at high altitudes. There were heated shoes that plugged into the suit, but they were light and not made for walking. I wore heavy walking shoes instead with heavy socks for warmth and for walking long distances in case I was shot down.

We were each issued an escape kit that contained a photograph of us in civilian clothes, maps, compass, chocolate, German and French money, and other items. My flight coveralls had a large buttoned pocket on the right leg below the knee where I kept my escape kit.

From there we went to the armament hut for our fifty caliber machine guns. We had to wipe almost all the oil off the guns because it got so cold at high altitudes that the least bit of oil would freeze and jam the guns. I have seen it so cold at high altitudes that spit would freeze before it hit anything..

We were then taken to “Murder Inc.” by truck. It took a large truck to carry ten men and all the guns and equipment.

Once on board we began to install guns and check equipment while waiting for the flare to be fired from the control tower to signal starting of engines. At last the flare was fired about sunrise. The pilot began starting the engines, but one engine was not working properly.

The pilot told the ground crew that this plane could not be flown because of the faulty engine. The ground crew said there was a standby plane ready to go and we would have to transfer to it.

The standby plane was named “Aristocrap” and was an unpainted aluminum color. The change bothered me because I feared the ground crew would not wipe enough oil off the guns. I did not believe they appreciated how cold it could get at high altitudes. At any rate, we transferred to “Aristocrap,” started the engines, and took off.

Changing planes had delayed us ten to fifteen minutes. When we got into the air we could not find the 351st Bomb Group since there were planes all over the sky. Finally we attached ourselves as the last plane, “tail-end Charlie,” to a group that was just starting out over the English Channel. I do not remember the identity of the group or the markings of their aircraft.

When we got out over the Channel we began testing our guns. There was a chin turret directly below me in the nose of the B-17 that I controlled remotely from my position inside the aircraft. The turret began to freeze as I tested it and finally froze beyond use. There was a flexible gun sticking out of the right side of the nose compartment that operated properly. The navigator also rode in the nose compartment with his flexible gun sticking out the left side. I reported the turret malfunction to the pilot.

As we proceeded on across the Channel my feet became extremely cold because I was not wearing heated shoes. During the next few minutes I experimented with putting my feet in direct sunlight and this did keep them warm.

When we arrived over Holland there were supposed to be American fighter planes to meet us and escort us into Germany. The sky was full of B-17’s but no fighter planes. I met a P-38 fighter pilot later in prison camp who told me they were over Holland at that time but could not locate us.

As we crossed into Germany I looked down and saw many German fighter planes taking off from a German airfield. Within minutes ME-109’s and FW-190’s were at our altitude firing at the formation. Then came the flak busting throughout the formation. We use to refer to flak this heavy as “so thick one could walk on it.” The German fighters ceased their attack and moved back so they would not be in danger of being hit by their own flak.

The flak continued as we passed over the target about noon. I did not aim the bombs. In formation flying the bombardier in the lead plane aimed at the target and all the other bombardiers simply dropped their bombs when he dropped his. As I watched the bombs fall away I prayed, as I had over Norway, that they would hit military targets only. Both the Germans and British used “saturation” bombing. In order to keep down their losses they would fly at night and drop bombs over a large area in order to ensure hitting their target. Both German and British airmen thought we were crazy to fly during the day and suffer the losses that we did in order to hit specific targets.

A burst of flak hit the chin turret directly below me and a fragment of it barely missed me as it flew up into the plane. I moved back to the flexible gun sticking out of the right side of the nose compartment. In moving back several feet I disconnected my microphone and earphones and lost communication with the rest of the crew. Flak knocked several large holes in each wing but all four engines were operating as we emerged from the flak. As we pulled out of the flak area the group to which we had attached ourselves began a turn to the right to return to England. We did not turn with them but kept flying straight into Germany. I assume the flak had damaged the controls and the pilot could not turn the plane.

When we were all alone in the sky many German fighters attacked our ship. Six ME-109’s lined up in formation about 1,000 yards out from my gun position, just beyond the range of my gun. I do not know how many fighters were at other positions around our plane. The first two German fighters turned toward us, one flying off the wing and just behind the other, and began firing their machine guns. Each fighter had six guns, making a total of twelve guns firing at me. Bullet holes began to pop in the window and side of our aircraft. Bullets flew all around me. I fired my gun at the fighters. The first two fighters passed below us and the next two came in for a pass, firing their guns. As they passed below us the last two came in. By the time they passed below us the first two were back in position and began another run. I always had two German fighters coming in on my position and I continually fired my gun at them. Not one bullet hit me nor did I shoot down a single German fighter.

I had lost communication with the rest of the crew but I sensed that something was wrong. I moved over from my gun position and looked back through the tunnel that led to the pilot’s compartment. The pilot was down in the tunnel banging on the escape hatch with a heavy ammunition box. Directly behind the pilot was a solid wall of flames. It looked to me as if the entire aircraft except for the nose compartment was engulfed in flames.

The escape hatch was on the floor of the tunnel. I crawled back to see if I could help the pilot open the escape hatch. As I crawled toward him the pilot put his foot on the hatch and forced it open. This took tremendous pressure since the slipstream was trying to force it closed. The pilot grabbed me by the waist and forced me head first out the escape hatch.

As I fell clear of the plane, my first reaction was a sense of relief that I had gotten away from that fire. My next thought was, “Did I put on that parachute?” I looked down at my chest — no parachute.

I felt something tugging at my shoulders and looked up. There a few feet above my head was my unopened parachute securely hooked to the risers of my harness. Evidently I had clipped the parachute on my harness but he force of the pilot pushing me through the escape hatch had ripped the risers loose, but the chute was still firmly hooked to the risers.

As I was falling, the pilot fell past me no more than fifty feet away. He had a look of horror on his face. I thought when we got on the ground I would kid him about how scared he looked. I found out later that both the pilot and the co-pilot had jumped without their parachutes. Evidently their chutes had burned in the fire.

They had told us if we ever bailed out in combat to delay opening the parachute so we could fall away from the fighting. I looked up at my chute and decided to open it right away. In case I had any trouble, I would then have time to work on it before I hit the ground. I pulled the parachute down to me hand over hand and pulled the ripcord. It opened immediately.

I did not realize the violent shock I would receive when the parachute opened. I was wearing a harness that was too big. The force of the opening jerked the harness up and tight around my throat. There I hung, about 20,000 feet over Germany unable to breath. I grabbed the risers and gradually pulled myself up in the harness until I could breath.

I had opened my parachute too close to the fighting and one of the German fighters came straight for me. I thought, “I have survived all of this just to be shot to death in my parachute by a German fighter.” But the fighter did not shoot at me. He circled me all the way to the ground. I assume he was radioing my position to the ground.

Next I realized how quiet it was. All I could hear was the sound of the breeze through my parachute. I was drifting backward in a strong wind.

I did not realize how hard I would hit the ground. My heels hit first – so violently that I did a complete backwards somersault. I was in a large field and the strong wind caught my parachute and began dragging me across the field. I tried to get up and run toward the chute to collapse it, but I could not run as fast as the wind was blowing. I tried to pull the bottom lines of the chute toward me to collapse it, but I did not have enough strength. Finally the bottom of the parachute caught on a barbed wire fence and collapsed, pulling me up tight against it.

The German fighter that had been circling me buzzed low over me. The pilot gave me a salute and flew away. Again it was very quiet. I looked down at my right leg for my escape kit. The right pants leg of my flight coveralls was torn away from the knee down – no escape kit. I struggled to get out of the parachute harness and just as I managed to free myself a German sergeant and several soldiers came over a small hill. The sergeant said, in a British accent, “Are you hurt, boy?”

I told him I was not hurt. Then he said, “What did you have for breakfast?” I replied, “bacon and eggs.” The sergeant then said, “I have not had bacon and eggs in a long time.” He told me he had lived in London for over ten years and hoped to go back there after the war.

The sergeant took me to his headquarters, an anti-aircraft installation. He got my name, home address and the fact that I am a Catholic from my dog tags. He kept telling me, “For you the war is over.” He sounded as if he envied me. He told in detail what would happen to me as a prisoner of war. I turned out that he was quite accurate.

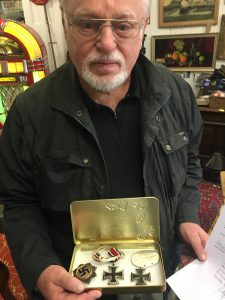

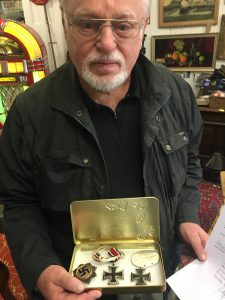

The sergeant said he had never captured a prisoner before and wanted to take some pictures. He took pictures of me front and back. The back pictures showed the “Murder Inc.” on my flight jacket. These were the only pictures the Germans ever took of the jacket and were the ones used in the propaganda.

Later that day I was taken by truck to a Luftwaffe base and locked in a small room. That night a Luftwaffe pilot came to my room and wanted to talk about airplanes. He did not speak English and I could not speak German, but we managed to communicate.

There seemed to be a bond among airmen, even on opposite sides of the war. We had been up there. We knew what it was like more than anyone on the ground would ever comprehend. It was as if “the war” was bigger than all of us and it was “the war” that was doing all the damage and was the real enemy to both of us.

The pilot said he had been a Stuka Dive Bomber pilot and was wounded in the leg over Malta. His leg was stiff and he had been grounded. He saw the “Murder Inc.” on the back of my flight jacket and told me I had better get that off. He said it might cause me some real trouble.

I sat up all night and picked that paint off of my flight jacket with my thumbnail. By morning all one could see was a faint outline of “Murder Inc.”

I heard no more about “Murder Inc.” while I was taken to Dulag Luft at Frankfurt (some solitary confinement there) then on to Stalag Luft I at Barth on the Baltic Sea.

I was Prisoner of War Number 1664 assigned to Block II (Barrack II). There were three barracks in the camp. Block III was completely empty. Blocks I and II held about 200 prisoners each, both British and American commissioned officer airmen.

On Christmas Eve, 1943, three German guards came to our room (about twenty men to a room) and said I was wanted by the German Commandant. They took me to the German officer’s club. It was decorated for Christmas with a Christmas tree and all the trimmings. The Commandant was seated at a table with two other men. He stood up, greeted me and shook hands. He asked me to have a seat and offered me some wine. I hesitated to drink the wine thinking it might be drugged, but the Commandant assured me it was good German Rhine wine, so I did take a few sips.

The Commandant said the man seated across from him had come up from Berlin to talk to me. The Commandant then stood up and said he had to leave, and he and the other officer left the table.

The man from Berlin was wearing a sweater (so no military rank) and military riding pants and boots. I believe he was a general from the way the Commandant, who was a colonel, had treated him. He was a good-looking man and appeared to be about forty years of age.

He asked me about Christmas in the United States and at my home. We wanted to know what I thought my parents would be doing at that time on Christmas Eve. I told him about Christmas Eve at home, exchange of presents, Midnight Mass, and about my family.

He then showed me a Berlin newspaper with my picture on the front page, a front view and the back view with the “Murder Inc.” on the back of the jacket. He said he had been sent up from Berlin to see if I were really a gangster. He said it was obvious to him that I was not a gangster and he thought that I would probably hear no more about “Murder Inc.” He wanted to know why we had given the plane this name. I told him I did not name the plane and did not know why it was so named.

He gave me the newspaper and said he thought I might like to have it as a souvenir. I have that very same paper in front of me now at my desk.

I was taken back to Block II and spent my first Christmas as a prisoner of war.

On December 28 they took me to the cooler (punishment prison) and locked me in a solitary confinement cell. About 5:30 the next morning two guards came and took me out the main gate of the camp and started walking toward Barth. It was just a short distance – maybe two miles. I asked “Where are we going?” They replied, “Berlin.”

I thought they were probably going to take me to Berlin, have a fake trial, and hang me in the public square so they could get more propaganda value out of “Murder Inc.”

At Barth we took a train and arrived in Berlin about noon. I was taken to an Italian and Russian prisoner of war camp located in the northern outskirts of the city. They put me in solitary confinement, but it was not so bad because I had a window to look out.

About noon on December 30 a German guard, who was over six feet tall and spoke good English, took me to the center of Berlin. We entered a large building and he said he was taking me to the Foreign Office. Inside we met a major who took me on an elevator to the fourth or fifth floor.

The major took me into an office that had a desk and several chairs. One man behind the desk told me he was Dr. Paul Schmidt, Hitler’s interpreter. He said the other man’s wife had been recently killed in an air raid. I thought they were telling me these things just to see my reaction. I had never heard of Dr. Paul Schmidt, but I have since learned that he was Hitler’s interpreter. I now believe that I was indeed talking to “the” Dr. Paul Schmidt.

Dr. Schmidt started by telling me that Germany was right in the war. He said that the countries around Germany were mistreating their German minorities and that Germany had to invade them to stop this. He asked me what I thought of Germany’s position.

I told him I understood that when Hitler first came to power during the Depression he started building roads, putting people back to work, improving the economy, and getting things rolling again. This was the same type thing President Roosevelt had done and I thought it was good, but when Hitler started invading neighboring countries that was bad.

I told him I thought they could actually have gotten away with it if they had not tried to conquer England, Africa and Russia. Their worst mistake, I said, was getting the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor. Then I said, “Could it be that you did not know that the Japanese were going to attack Pearl Harbor?” There was no response, but from their reaction I believe they did not know about the attack in advance. They simply said something about the Japanese being a great people.

At any rate, I told them that once the United States had entered the war, Germany did not have a chance to win. The asked me if I thought the American soldier was superior. I told them no, it was the production power of the United States that would overwhelm them.

Dr. Schmidt said that all Americans were overly optimistic and began trying to convince me that Germany was going to win the war. He must have thought he had me convinced because he said that not all prisoners of war lived in prison camps. Some, he said, lived in Berlin in nice apartments and had their freedom within the city, went to the theatre, had girl friends, and lived a pleasant life. He then said he was not without influence in the government and he thought he could probably arrange for me to have just about anything I might want. He then inquired, “Is there anything you would like for me to do for you?” In response I said, “Yes.” His face lit up and he inquired, “What can I do for you?” I said, “Take me back to the prison camp and leave me alone.”

Having said he could do just about anything for me, he actually seemed apologetic that he could not do the simple thing I had asked. He said it would not be possible for to return to the prison camp right away. There were other people in Berlin who wanted to see me. He wasn’t sure how many persons I would talk with or how long I would be kept in Berlin. (I believe this conversation took somewhere between one and two hours. I feel certain it was recorded through a hidden microphone and could very well still be on file somewhere in Berlin.) Eventually I was taken back to the Italian and Russian prison camp and the solitary confinement cell.

The next day, Friday, December 31, I saw a British prisoner of war out in the compound with the Italian and Russian prisoners. I had a guard stationed outside my door at all times. This guard would escort me across the compound to the toilets on the far side. The next time we were crossing the compound I managed to speak to the British prisoner.

A few days later the Englishman pushed a note through a crack in the wall separating my room from the one he shared with some Italian prisoners. He wanted to know what I was doing there. I told him about “Murder Inc.” He sent a note back wanting to know why we had given a plane this name. I told him I had nothing to do with naming the plane and had no idea why it was so named. The next day he pushed a note through saying that he was a Catholic and that the Germans allowed him to go to Mass in town on Sundays. He said if I would write down a prayer the priest would put it on the altar and include my intentions with the Mass. I wrote a prayer that the war would end and for my family back home, and then I pushed what I had written through to him.

During the next few days he got my entire story by our pushing notes back and forth. He told me that before the war he had worked at White Hall in London. As best as I can remember he said his name was Rufus L. Yates, but after all these years, I cannot be sure. He began to send me food, cigarettes, religious books, and cards through the German guard that was always stationed at my door.

One day about a dozen generals and their aides from the Luftwaffe, SS, Army, and Navy came to the camp. The guard outside my door came in and pointed to them through the window. He seemed proud that these important people had come to the camp. He pointed out the different ranks and different organizations. He tried to explain to me the difference between the SS and the Gestapo. He said these important people assembling here had something to do with me. He seemed to think I should be proud of such an honor.

The generals went into the mess hall. I expected to be called to appear before them. After about an hour or more they came out got into their automobiles and left. (I had not seen so many cars in one place since I had been in Germany.) I did not appear before them, but I am sure they looked at the evidence that had been gathered and decided to send me back to the prisoner of war camp.

Early on Sunday, January 9, 1944, the same two guards that had brought me to Berlin came into the room and woke me up. They took me by train back to Barth and out to Stalag Luft I. I spent the rest of the war at Stalag Luft I. The prison camp grew from the three barracks mentioned earlier to about fifty barracks holding about 10,000 American officers. No more British officers arrived and the ones there were put into separate barracks. We were in the South Compound with the British officers. Most of the prisoners were in the North Compound and completely separated from us.

I did see more pictures and cartoons in German newspapers about “Murder Inc.” One day a fellow prisoner showed me a German magazine that he said was running the story of my life in serial form. (I do not read German). He said the magazine said I was one of Al Capone’s gangsters in Chicago and had finally gone to jail in Alcatraz Prison. When the war started, the magazine reported, President Roosevelt had gone to the warden of Alcatraz and told him that he wanted the meanest man in the prison to go over and kill German women and children. The article also stated the warden told Roosevelt that Ken Williams was the best man for the job. According to the magazine, Roosevelt then arranged for me to get out of prison and organize the effort, entitled “Murder Inc.” to kill German women and children.

Not all of my memories of prison camp are unpleasant. We played bridge, chess, poker and other games. We played volleyball, baseball, football and other sports. On the train from Berlin back to Barth a girl gave me a piece of cake after the guards had already told her I was a prisoner of war. On that trip the guards took me into a beer hall and bought me a beer. We had a radio at Stalag Luft I that the Germans could not locate. Some of the men listened to B.B.C. and wrote a newsletter that was circulated throughout the camp. Someone was always digging a tunnel to try to escape.

Some memories are not so pleasant. One man was shot dead, not fifty feet from where I was standing, for stepping out of his barracks during an air raid. I saw one prisoner, who had lost his mind fall to the ground, and a guard put a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger but the gun misfired. Lawton H. Wilkes, the right waist gunner from my crew lost his mind while confined to Stalag 17-B and ran screaming across the compound. He started climbing the barbed wire fence and was shot dead by the guards. The stress of the war and prison camp caused some to lose their minds. I saw our chaplain (Father Charlton, an Irish priest who was in the British Army) step between a hysterical guard and a prisoner, calm the guard down and keep him from firing his machine gun at the prisoner. The worst things for me personally were solitary confinement and starvation. I lost from 150 pounds down to almost 100 pounds.

At the end of the war the Russians took over that part of Germany and liberated us on May 1, 1945. We had trouble trying to make arrangements with the Russians to get back to our own people. But eventually the Eighth Air Force sent in B-17’s and flew us to France on May 14, 1945.

Of the ten men on my crew, six survived the war. The pilot (Orvil L. Castle) and copilot (Leon E. Anderson) were killed when they jumped without their parachutes. Mike C. Beckett, the radio operator was shot to death in the plane and Lawton H. Wilkes, the right waist gunner was killed in prison camp.

From Camp Lucky Strike in France, I boarded a ship at Le Harve and arrived back in the United States on June 21, 1945, to take up my civilian life. On September 1, I married my childhood sweetheart Jean Lorraine Zeman. Over the years we had five children – four sons and one daughter. I was discharged from the Army Air Corps on December 11, 1945, and went into the business of manufacturing warm air furnaces. On February 13, 1956, I went to work for the local city and county governments as Civil Defense Director. The title of this job changed several times until I retired on October 25, 1983, with the title of Emergency Management Director. After more than thirty-eight years of being happily married my beloved wife died of cancer on March 30, 1984. This was a devastating experience.

Right after the war I received hundreds of letters from all over the world. All of the letters were supportive and wished me well. They all contained newspaper clippings of “Murder Inc.” that they thought I might like to have as a souvenir. Many were anxious to know if I had survived the war. There were so many letters I could not answer them all, so I regretfully decided not to answer any of them. I put the letters in a box and stored them in a closet. A slow leak developed in a water pipe and dripped on the letters over a period of time. Several years ago I took the box out of the closet and the letters were ruined, turned to pulp. I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to any of the people who may read this and were so kind as to have sent me one of those letters.

I did bring home the jacket that had caused all the trouble. I had “Murder Inc.: painted on again exactly as it had been before I spent one night removing it. The jacket is old and stiff now and the lettering has faded, but I am wearing it as I write this.

In closing this narrative I pray to God that there will never again be another World War.